Evidence-based policymaking: How to actually get policymakers to listen

Evidence-based policymaking (commonly abbreviated as EBPM) has been a concept and buzzword across the policy communities for a while now. It refers to the idea of rigorous scientific evidence being used to create rational policy solutions to solve a policy problem.

Everyone agrees that evidence-based policymaking is a good thing.

Who would deny it in fact? No one would.

But sadly sometimes good evidence doesn’t lead to policy.

Don’t Kill the Messenger

A standout example when good evidence didn’t lead to policy change is the sacking of Professor David Nutt from a decade ago.¹

Prof. Nutt gave a talk and answered a question about drugs in the UK and outlined that many illegal drugs in the UK were in fact less worst overall than alcohol. He gave this statement in the context of the then-Labour government trying to appear hard on drugs through the reclassification.

Que political fallout for the then-government and sacking of Nutt.²

It’s an example of a well known scientist-academic saying something at the wrong time and place and then getting the sack for it.

The Politics of evidence-based policymaking?

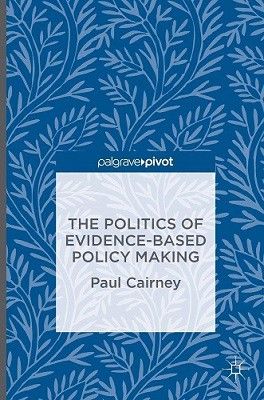

Paul Cairney is a professor of politics and public policy from the University of Stirling. In his short book The Politics of Evidence-based Policy Making he analyses two policy areas to find the types of common barriers, how to overcome them, and how to influence policy.

Cairney explains the concept of EBPM, the underlying theories behind it and approaches by scientists and policymakers, examples of barriers, and lessons learnt from two distinct policy areas.

Evidence-based Policy Making: Guidelines to Follow

Pack evidence better, include some persuasion

Simplifying research into layman terms for policymakers or press releases is important, but dry language isn’t going to sell your policy proposals. Policymakers are under time pressure and take mental shortcuts. Take advantage of this in your persuasive language and reframe your arguments if you have to.

Build relationships and learn how to conduct yourself

Advocates need to build relationships within government, by being seen as reliable and knowing ‘the rules of the game’. Being trusted means government departments are more likely to ask you for your views in a short period of time. It also takes time to build a willing coalition for change. Having those relations built up beforehand will only put you in good stead.

Don’t just focus on central government

Most policies in the UK are deliberated on by relatively low level civil servants and then delivered by public bodies and local government. Focusing efforts totally on centralised government and elected policymakers (read: politicians) probably isn’t the best use of resources.

Realise that Evidence-based Policymaking is a highly charged political process

The case of tobacco shows that evidence is not always enough. Campaigning over several decades reframed arguments around tobacco and highlighted the negative health effects as an epidemic. Tobacco is an example of successful campaigning which changed views of it as an economic benefit to a health negative.

Keep an open mind with people

Scientists do not engage well with policymakers. Scientists also don’t deal well with scientists from other disciplines! This causes delays in knowledge transfer and the impact of findings. Keep an open mind and engage with people for a smoother delivery.

Keep an open mind with research and evidence

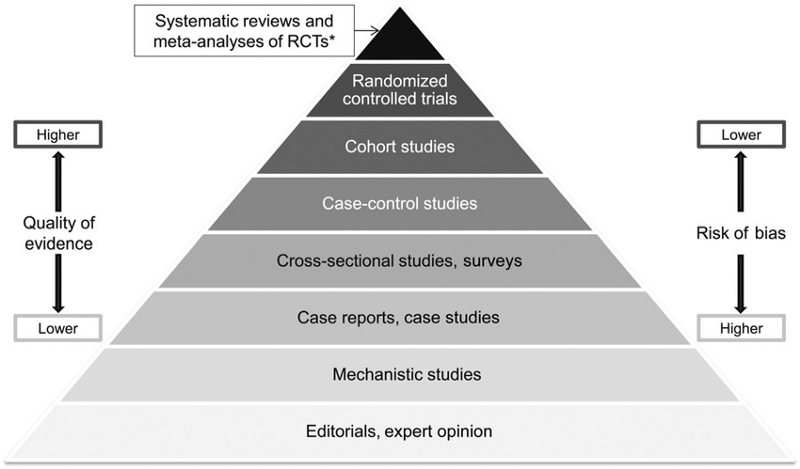

Use a mix of evidence to persuade policymakers. Large Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) are often seen by researchers as the gold standard on top of a hierarchy of evidence types. But case studies, anecdotes and other qualitative evidence can often be more persuasive and an easier sell to elected policy makers. Remember. You’re dealing with people. Not your colleague scientist.

It’s How We Communicate

Sometimes scientist-researchers need to be told that it’s OK not to sound like a robot. How we communicate is important, if not more, than the content of what we say or write.

Policymakers aren’t researchers. Treating themselves as such will only lead to disappointment for everyone involved.

Dealing with the reality of the world means advocates have to tailor and reframe dry evidence into persuasive and engaging evidence to different audiences.

Don’t just send someone an executive summary or full report!

Footnotes

- The Professor David Nutt episode is a very common anecdote in policy and health studies in the UK. It’s so well known that I see it referenced to this day by academics, journalists and normal people in print and occasional conversation.

- A year after his dismissal Professor David Nutt, with a number of co-authors, published a study in the Lancet which empirically corroborated his previous comments.

Note: This blogpost was originally posted on Medium in August 2019.